What is Zazen?

Realized in unity, it is a whole which is greater than the sum of two parts -- two parts which are in antagonistic opposition to each other.

The ZA part expresses the physical act of sitting, requiring a physical effort guided by the faculty of feeling.

The ZEN part expresses the mental act of meditating/thinking, requring an effort based on a faculty which is not a slave to feeling.

When ZA and ZEN truly become ZAZEN, it is not a physical or mental effort, but a Dharma-gate of effortless ease.

Bonnie Bainbridge-Cohen wrote an excellent book called Sensing, Feeling & Action. If I intended to write a book, which for the present I don’t, I might call it Feeling, Thinking & Action. For Master Dogen’s purposes, I think the latter title would be more to the point.

Gudo Nishijima’s Zazen teaching, in a nutshell, is: not the parasympathetic-nervous-system-dominated state of feeling, not the sympathetic-nervous-system-dominated state of thinking, but just the balanced state of action. In short: Not Feeling, Not Thinking, Just Action.

This is Gudo’s Buddhist thesis.

My anti-thesis is simply this: Feeling and Thinking and Action.

My Buddhist master’s understanding is based on nearly 70 years of sitting in lotus. My understanding is based on only 25 years of sitting in lotus. But my understanding is also based on 12 years in the Alexander work, whose true value is very difficult to suppose, for a person who has not experienced it deeply in practice.

People who think that Alexander work is a kind of bodywork, are wrong.

Alexander work begins with the recognition of what FM Alexander observed to be a universal defect: “unreliable sensory appreciation.” First he discovered it in himself; then he noticed that he wasn’t the only damn fool who felt himself to be right when the mirror showed him to be wrong. In civilized society, we are almost all like that -- misguided by unreliable body-feeling. Ray Evans, my Alexander head of training, was ahead of the game in seeing the connection with immature primitive reflexes.

Clearly understanding that body-feeling is unreliable, Alexander got himself going in the right direction by trusting something other than his feeling. What was it? Some kind of intuition? In his first book he called it “Man’s Supreme Inheritance.”

The full title was Man’s Supreme Inheritance -- Conscious Guidance and Control in Relation to Human Evolution in Civlization.

People are prone to think about Alexander work as all about posture -- which in a secondary sense it is. But for FM Alexander himself, the work was primarily about consciousness and thinking and rationality. He described his work as an exercise is finding out what thinking is.

Thus, in writing of psychophysical unity, in other words, unity of mind and body, Alexander put mind first.

Master Dogen, conversely, wrote of unity of body and mind, and dropping off of body and mind. Following the example of Master Tendo Nyojo, he always put body before mind. This is vital to understanding Master Dogen’s teaching, which is always rooted in regular physical practice of Zazen, with the body seated in the traditional full lotus posture.

Although body-feeling is an unreliable guide, I rely on it, as a starting point. As a seeker of Gautama Buddha’s truth, irrespective of whether my feeling is right or wrong, primarily I put my trust in this physical sitting posture.

But because body-feeling is an unreliable guide, I also put my trust in another faculty, which -- even if it is not human reason per se -- is at least informed by rationality. Two and two, for all practical purposes, is always four. Reason is reliable. But on its own reason is powerless. Therefore in Zazen practice I put my trust not only in the physical posture, but also in rational intention, volition, thinking.

Originally dhyana just means thinking.

In a recent email to me, Gudo wrote as follows:

You wrote that "The original meaning of dhyana, as I understand it, is just ‘thinking.’” But I can never agree with such an idea. After my more than 60 years of study, I would like to insist clearly that "The original meaning of dhyana is just the balance of the autonomic nervous system."

* * *

My reply to Gudo was as follows:

You describe that, when you notice that you are thinking something in Zazen, you bring your consciousness back to the state that you call balance of the autonomic nervous system. You identify dhyana with the original state to which you wish to come back -- i.e. in your words, balance of the autonomic nervous system. But the true meaning of dhyana, within your own description, if we follow the literal meaning of the word as per the Monier Williams Sanskrit dictionary (dhyana = meditation/thought), is not our original state. Dhyana is rather the effort to "bring consciousness back," i.e. the effort to re-direct consciousness. This effort also is a kind of thinking. Therefore Master Dogen instructed us: Think that state beyond thinking.

* * *

The great value of Alexander work, to me at least, has been to clarify what kind of thinking dhyana is.

Although the aim of Zazen, Sitting-Dhyana, is a state of effortless ease which is beyond thinking, I pursue this state through physical and mental effort. I make my one-sided effort on the unreliable basis of body-feeling, and make my opposite-sided effort on the impossible basis of mind-thinking.

In Fukan-zazen-gi Master Dogen instructs us:

Having regulated the physical posture, breathe out, sway left and right, and then, sitting still, think the state beyond thinking. How can the state beyond thinking be thought? Non-thinking. This is the vital art of sitting-dhyana. What is called sitting-dhyana is not a kind of dhyana to be learned. It is the Dharma-gate of peace and ease. It is the practice and experience that perfectly realizes the Buddha’s enlightenment. The laws of the Universe are realized, there being nothing with which a dragon or a tiger might be caught or caged.

So what is Master Dogen saying about thinking? I understand that Master Dogen is saying, with Alexander, that, yes, because body-feeling is unreliable, we should rely in Zazen on the faculty that is opposed to body-feeling, that is, the mental effort of thinking. So he says: “THINK that state beyond thinking.”

This understanding that I am saying now is totally different from what Gudo Nishijima has taught me. In my view, his teaching on this point is not accurate and not reliable. He is prejudiced against thinking.

Master Dogen instructs us: “Think that state beyond thinking. How? Non-thinking.”

With regard to HISHIRYO, “non-thinking,” Gudo Nishijima is adamant that this expresses action itself, sitting itself, which is different from thinking. But I am not convinced by that argument either.

I may be wrong on this, but my understanding now is that Master Dogen not only exhorts us to make a mental effort with the imperative “Think that state beyond thinking,” but also points us in the same direction with the words “Non-thinking.”

My anti-thesis to Gudo’s thesis is this: HISHIRYO, “non-thinking,” expresses not action itself, but rather thinking itself, the mental effort which is antagonistically opposed to bodily effort based on feeling.

In Shobogenzo Master Dogen discusses the term HIBUTSU, “non-buddha.” Non-buddha means a true buddha, a real buddha, a buddha whose reality is contrary to habitual conceptions of buddha, a buddha whose reality is contrary to what people are prone to feel and think buddha is.

Similarly, I suggest, HISHIRYO means thinking, real thinking, real intention, real volition -- thinking whose reality is contrary to our habitual conceptions of thinking.

This real thinking is thinking of the kind Alexander described -- “Thinking, but not what you understand by thinking.”

Master Dogen goes on to stress that:

IWAYURU ZAZEN WA SHUZEN NI WA ARAZU.

What is called ZAZEN “Sitting-dhyana” is not SHU-ZEN “learning-dhyana.”

What is Master Dogen denying? I think that Master Dogen is stressing that the ZEN part of ZAZEN, the thinking part, the mental part, is not something that we have to learn. It is something that, in Zazen, we have the opportunity to re-discover.

This tallies with Master Dogen’s main message in Fukan-zazen-gi: Zazen is not an effort to bring enlightenment into being, not an effort to learn how to become Buddha; it is rather an effort to be taken over by the all-pervading enlightenment that already exists within us and around us, an effort to stop not being Buddha. The point is not to learn something new. It is to discover our original inheritance, to let open the treasure-storehouse which is our birthright.

Master Dogen’s intention, as I understand it now, is that the kind of thinking he is exhorting us to practice is not sophisticated, not intellectual, not pretentious, not insincere, not unreal. It is not a faculty that we have to learn. It is a faculty we have had since our first voluntary movements and non-movements in our earliest infancy.

My original state is one of peace and ease, and I wish to come back to it. Just that. What should this wish be called? Volition? Clarity of intention? Thinking? Non-thinking?

Alexander used to say: “This work is an exercise in finding out what thinking is.” This is subtly different from saying “This work is learning thinking” or “learning how to think.”

The great difficulty that I encounter in hands-on Alexander teaching work is not that I haven’t learned how to think: I already know perfectly well how to think. I have known since I was a baby. The difficulty is that in my practice here and now, I do not trust the incredible tangible power that a thought has. Without the assurance of feeling something that feels right, I don’t feel secure, and so my hands are taken over by a grabbing response.

When my Alexander teacher, after her 45 years in the work, puts her hands on me, I experience without any doubt the power of a thought. Her hands do absolutely nothing; they are just there. And yet something flows through her hands and seems to dig my head out from the depths of me, from the very soles of my feet. She calls this something “a thought.”

“It is a kind of wish, isn’t it?” I asked her once. “Yes,” she replied, “but it is a wish that won’t take No for an answer.”

In other words: “It is a wish, but not what you understand by a wish.” It is stronger and more real than that. Non-wishing.

When I myself am in the teaching role, at the critical moment when I wish to cause the pupil to rise from the chair, I am prone to feel that I have to do something with my hands and so I do something with my hands -- instead of just leaving them open and allowing them to transmit a thought. When, with the teacher’s help, I am able to inhibit this doing/feeling response, then something truly magical happens.

The miraculous power of a thought. A wish that won’t take No for an answer. Whatever we call it, it is a kind of mental effort that goes against the body’s habitual stream of activity which is pulled along by unreliable feeling.

Finally, I come back to my favourite three sentences from Shobogenzo chapter 72, Zanmai-o-zanmai:

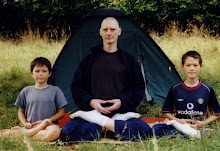

Practice bodily sitting in the full lotus posture.

Practice mentally sitting in the full lotus posture.

Practice body and mind dropping off sitting in the full lotus posture.

It is like the Earth’s gravity pulling at a green leaf, which a tree won’t drop. The leaf turns golden and the tree pushes it out, but still the leaf won’t drop. When the wind blows, and the leaf floats free, we should not say that it wasn’t gravity, and should not say that it wasn’t the will of the tree. We should not say that it was only the wind. It was gravity and the tree and the wind, altogether and one after another.