The Truth Will Out in the End

Between 1982 and 1990 I lived in a flat in Sugamachi, about a ten-minute bicycle ride from Ida Company HQ in Iidabashi, where, from 1983 onwards, Gudo’s office was. (Before that the office was further away, in Asakusabashi.) From the local Marusyo supermarket I would buy notebooks with lines of squares designed to help children practice writing, and in these children’s notebooks I would write out sentences from Shobogenzo in pencil, and mark bits I wanted to ask about in red ink. There is a film record of me doing just this from a 1989 BBC documentary called “Turning Japanese” in which my life in Tokyo was featured. With my children’s notebook of questions, and Gudo’s blue book containing Master Dogen’s original text and and Gudo’s translation/interpretation in modern Japanese, I would cycle down to Gudo’s office to ask my questions. I would phone him up and ask if he was free, and the answer was invariably, “Oh, please come!” Rarely I would have to wait an hour or two for a business meeting to finish, but there was never a case of “I don’t really feel like it today -- I am not in the mood.” Just “Oh, please come.” I would sit there in the office slavishly dictating Gudo’s answers to my questions, and then cycle back home and type up my notes onto a personal computer.

After I got married and moved out to Bushi on the outskirts of Tokyo, where we lived from 1990 to 1994, I used to write my questions on the meaning of Shobogenzo in thick felt pen on A4 sheets and fax my questions in to Gudo’s office, and he, in similar style, used to fax the answer’s back.

I thus asked questions on the meaning of Shobogenzo almost non-stop from the time I first met Gudo in the early summer of 1982 right through to 1994 when Shobogenzo Book One was published. Over this 13 years of questionning, I must have asked Gudo several thousand questions on the meaning of Shobogenzo.

Incidentally, between 1986 and 1988 I would go to Gudo’s office on Thursday afternoons to take his dictation of Shinji-Shobogenzo, and then accompany him to his Japanese lectures of Shinji-Shobogenzo in Asakusabashi. Back in my flat, I would sit at the computer, basically transcribing the dictation, but with one eye also on the original text. I felt the fact that I had sat there absorbing the Japanese lectures somehow lent more authenticity to the work. By the spring of 1988, I had transcribed most of the 301 koans, but I then gave up work on the Shinji-Shobogenzo dictation in order to concentrate on Shobogenzo itself. If you read the published version of Shinji-Shobogenzo, you won’t find my name featured too prominently. Apparently this was because, by the time the work was published, Gudo had forgotten who it was that began taking the dictation -- he thought it had been Jeremy Pearson. Michael Luetchford and Jeremy Pearson completed the project without supposing the amount of work that I had put into it. (This is not to take anything away from the considerable effort they evidently put into the project themselves.)

I digress. In the spring of 1988, while I was in Thailand, Gudo wrote me a letter asking me for my full cooperation with the Shobogenzo translation. He asked me for five years. I gave him those five years, and more. In return Gudo started paying me a “scholarship” of Y50,000 per month. This scholarship continued even after I returned to England at the end of 1994, and didn’t stop until around the time that Gudo wrote me a letter -- I think it was towards the end of 1996 or in early 1997 -- expressing his hope that I would “come back to Buddhism.”

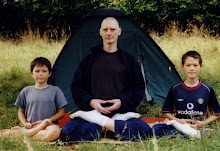

In addition to the scholarship, in view of my desire to provide for two sons born in 1991 and 1993, Gudo generously agreed to forego his half of the money which we received for the translation from the Japan Foundation.

Our translation partnership was a totally joint effort. “Fifty-fifty” in Gudo’s own words, but those words didn’t do it justice. The fundamental principle of the partnership, as I understood it, was that of the mutual veto. Neither side was allowed to change the translation text without the consent of the other.

This was the fundamental rule of our partnership that I never, ever, expected Gudo to break. Why would he need to? If he wanted me to correct some mistake I had made, all he had to do was ask. But in 1997, during the final editing of Master Dogen’s Shobogenzo Book 3, Gudo decided to break the rule. Apparently he felt he needed to put his foot down, lest some stupid person adulterated the pure, practical teaching of Master Dogen with a different kind of knowledge, borne of “Western intellectual civilization.” (Heard any good jokes recently? Spotted any examples of the mirror principle?)

Breaking the rule wasn’t a mere oversight on Gudo’s part. There was a meeting in Tokyo in which a conscious decision was taken to make changes to the text without consulting me in England. The meeting was initiated, as I understand it, by Michael Luetchford. But the decision to blank me was taken in the end by Gudo himself, together with Michael Luetchford, and overriding the objections of Jeremy Pearson.

When I heard from Jeremy what had happened, several months later, after Book 3 was already published, I went into shock. I couldn’t believe it had happened. I gave up translation work and retreated into my own sitting-zen/Fukan-zazen-gi. At the same time, I retreated into denial.

Now then, how can I spring this 47-year old body of mine, which is ordinarily governed by a dodgy vestibular system, totally free from denial?

A very interesting question.

Before trying afresh to ask it well, I wouldn’t mind forty winks.

2 Comments:

;-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-)

;-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-)

;-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-)

;-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-);-)

After an afternoon of sitting-zen, I can’t make any claim to have sprung out of denial. The best I can claim is to notice afresh how deeply I am in denial.

I notice that what has deserted me, as repeatedly in the past, is deep belief in cause and effect.

Any hint of blaming others for shocks that I have received in my life, is a kind of denial of cause and effect.

Everything that has happened to me, all the happiness and all the disappointments, I have deserved.

If Michael Luetchford and I arrived in the hands of a carpenter at a stage in his career when his woodworking skills were not so subtle or refined, we got exactly the carpenter we deserved when we deserved to get him.

Not only that -- MJL and I fully deserved to bump into each other! And if we two guys cannot have true compassion for each other, born of understanding of the causes of our individual suffering, then who on earth can?

Post a Comment

<< Home