Being Without Sincerity

As a result of the above circumstances, I happen to know that the original meaning of the word "sincere" is the Latin SINE CERA, or without wax. If you were a Roman centurion sending some important official document, you would seal it with wax. But if you were sending something straight from the heart, say, an ode to your girlfriend, you would send it without wax.

For Gudo Nishijima, being without wax is a big thing. We his Dharma-heirs tend to think of ourselves as sincere people. We don’t like to think of ourselves as insincere. Still less do we like to think of our Master as insincere.

I remember attending a Saturday-afternoon lecture in Tokyo in 1983 or 1984 on Shobogenzo chapter 5, Ju-undo-shiki, which contains the sentence "Now that each of us is meeting what is hard to meet and is practising what is hard to practice, we must not lose our sincerity. This [sincerity] is called the body-and-mind of the Buddhist patriarchs." The lecture stuck in my mind because Gudo made such a great point of emphasizing the importance of this sentence, now important it was for us to be sincere.

In this chapter, “sincerity” is a translation of the Japanese words MAKOTO NO OMOI. MAKOTO NO means true, real, genuine. OMOI means thought, mind, heart, wish.

Elsewhere in Shobogenzo “sincerity” is represented by the two Chinese characters SEKI-SHIN, literally “red mind.” Red mind means naked mind, mind that is not covered up, for example, by sophisticated intellectual pretensions.

Not even then the pretension to be sincere.

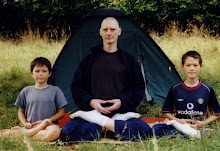

I joined Gudo in 1982, several years before he got the idea to establish a multinational group called “Dogen Sangha.” The group he led at that time, for an annual Zazen retreat and weekly lectures on Shobogenzo, was called SEKI-SHIN-KAI, The Red Mind Club.

During the 1980s, as a keen young member of The Red Mind Club, I felt part of something that was a cut above any other kind of Zen group. We were the truly sincere ones, the sincere Zazen practitioners. We were not like the scholars who studied Shobogenzo only intellectually, as if counting grains of sand on the sea-shore. We were not like the professional priests who claimed to belong to the so-called “Soto Sect,” devoting themselves to making money from holding funerals and tending graves.

We were the sincere ones, the ones who had no fish to fry.

Except: from where did this attachment arise to the theory of balance of the autonomic nervous system as an explanation of the “real content of enlightenment”? Out of nowhere? Out of nothing? Out of sincerity itself?

No, the truth is that we were not and we are not the sincere ones. We are human beings, in the same boat as everybody else. Sometimes we are very sincere. Sometimes we are very insincere.

Zazen gives us the opportunity of experiencing ourselves as we really are, in all our sincerity and also in all our insincerity.

If, falling in love with the idea of my own sincerity, I can’t face up to the fact of my own insincerity, I am liable to react to the latter fact in all kinds of deluded ways.

First of all, I may try to deny it:

* “If FM Alexander’s idea is the same as [my] Buddhist idea, I need not study the idea of FM Alexander. If FM Alexander’s idea is different from [my] Buddhist idea, his idea must be wrong.”

* “If some rude person says that Gudo is insincere, that his teaching about the autonomic nervous system arises just out of insincerity, just out of intellectual pride, then the reason he is saying it is only because he is a total prick. Or else because he is mad--out of compassion for all living beings, let him be asked to leave Dogen Sangha.”

Or for another example of deluded reaction, there is anger. For that there is an ample resource of more than ten years of my emails.

Or for another example of reaction, deluded or not I don’t know, there is silence. Who knows what emotion or non-emotion might be shrouded in the silence of Dharma-heirs such as Michael Luetchford, Gabriele Linnebach, Jeremy Pearson, Taijun Saito, Denis Legrand, Luis, Herve, Rachel, et cetera, et cetera.

Maybe shame? Maybe fear? Maybe bewilderment, confusion?

Who am I to say? My frank perception is that there is a fair degree of cowardice operating. People who are nominally devoted to pursuit of the truth are actually afraid of facing the truth.

I do not exclude myself from this criticism. On the other hand, I have had something that has really helped me in the direction of seeing my insincerity for what it is. I have had exposure to the teaching of FM Alexander.

Alexander said, “The most difficult things to get rid of are the ones that don’t exist.” He said it; he saw it; he knew it.

Insincerity does not exist. In the clear staccato warbling of a dunnock, where is there wax? Originally there is no wax anywhere. And yet, it seems, wax is very difficult to get rid of.

Old FM knew that in order to liberate ourselves from insincerity, we have to know what insincerity is, we have to face it, we have to truly see it, to know it, first and foremost in ourselves.

What does it mean truly to be liberated from our own insincerity?

It means being without, being bereft, all pretensions and conceptions dropped off. In short, it means just to sit, sincerely.

The criterion for this sincerity is the samadhi of accepting and using the self.

Samadhi is stillness without fixity. Don’t try to fix it; don’t try out of intellectual pride to grab it with a theory about the autonomic nervous system. That kind of intellectual grasping is just insincerity. And don’t I just know it?

7 Comments:

Alexander expressed it as "to allow the head to be released forward and up, to allow the back to lengthen and widen."

But to sincerely allow such a response in myself, and to cleverly manage a situation, are utterly different things.

All my upbringing, from being top of the class at primary school, to captaining the school rugby team and being captain of the university karate club, to studying management at university, to aspiring to be a five star Zen Master ever since then, pushes me in the latter direction -- not in the direction of being a sincere allower but in the opposite direction of being a clever manager.

So we can express it as "allowing," but truly to allow it in myself, even for one moment, is an utterly different matter.

A true Zen Master, as I see it now, is not a clever manager of others but a true allower of herself.

She expresses it as allowing, she practices it as allowing, and she experiences it as allowing.

In Shepherds Bush, where I grew up and where I was never top of anything, intellectual grasping is called disappearing up your own arse.

Mike, could it be that the silence of some of Gudo’s “Dharma-heirs” is because they don’t give a toss?

Or as kids say “They can’t be arsed.”

Time to sit on my arse before I disappear up it.

Cheers

Pete

Who knows? Could be that one or two of them are following the precept not to engage in useless argument. (Following that one is not my strong point.)

But of the silent ones, I know of at least one whose feeling about the Old Man is that of shame.

And of the non-silent ones, Brad Warner seems to me to be deeply in denial.

"Who knows? Could be that one or two of them are following the precept not to engage in useless argument. (Following that one is not my strong point.)

But of the silent ones, I know of at least one whose feeling about the Old Man is that of shame.

And of the non-silent ones, Brad Warner seems to me to be deeply in denial."

Mike, possibly so.. denial or loyalty. Maybe Brad is just being loyal to a teacher he loves and is grateful to.

Master Gudo is 87? years old. If he is slipping because of his advanced age, what kind of person would feel anything but protective towards him?

Is it even possible to revoke Dharma-Heirdom? That would mean

a) the master didn't see correctly through the person which would render him unable to give Dharma-Transmission to anyone in the first place.

or

b) all efforts whe do in zazen and other buddhist stuff can and will fade in the end. All achievements would be devaluated, as they are not persistent but maybe only will last for an instant.

c) If there is this eternal truth that we can achieve and lose, it was no real truth in the first place, as it didn't keep us from losing it.

How depressing...

Thank you, Oxeye

I have never for a moment questioned Brad's loyalty to Gudo.

But is it not often the case, when one looks into the mirror of history, that loyalty and denial go hand in hand?

Am I simply fooling myself when I hold onto the belief that, what may seem to others, and what may seem to Gudo himself, to be disloyal behavior on my part, is in fact uttterly loyal behavior.

The real teaching of Master Dogen, to the propagation of which Gudo has devoted his life, is not about loyalty to some sectarian doctrine; it is to wake up to reality.

Gudo’s idea about the importance of his theory about the autonomic nervous system is just a fantasy. To see that clearly, and to say so, is not in reality a sin -- even though, to sravakas, it looks like it.

Brad is not a fool. Maybe Cohen is, an out and out fool, but Brad is not. If his will to the truth is genuine, he will change his tune, sooner or later.

It is not that I am such a great wonder. I am not. But the principles of FM Alexander’s teaching are just true.

The answer to your question, Docreto, is yes and no.

I can disown my son. I can say to him, “You are no longer my son,” and cut him out of my will. Legally he may cease to be my son. But in reality he will always be my son, and I will always be his father.

Post a Comment

<< Home