Preamble (2): On Arrogance & Imperialism, Modern Psychology, Seeking Ease in Suffering, Not Being Up to the Task, Etc.

Certainly there can be institutional intellectual arrogance -- when I was 10 years old I passed an entrance examination in order to attend one such elitist institution, called King Edwards School, Birmingham. Founded in 1663 (I think), the school churned out more than its fair share of builders of the British Empire. Even at Oxford and Cambridge, we were told, KES boys had a reputation for being deep thinkers.

If might makes right, does that mean that the cultural or racial arrogance of empire-builders is justified, for a while?

What kind of elite is going to be the builders of the next great empire?

What role in that empire might be played by Master Dogen’s rules of sitting-Zen FOR EVERYBODY? A unifying role? A subversive role? A negligible role? None of the above?

It seems to me that several excellent Buddhist teachers in the world today have not only a background in ancient religious wisdom but also some grasp of modern sciences such as psychology. James Cohen, whose heritage appears to be Judaism, may be one example. Richard Morrissey, whose heritage appears to be Christian, may be another. The Dalai Lama, whose heritage is evidently Buddhist, is another.

Meanwhile, the criterion that precedes knowing and seeing is manifested in actions like brandishing a fist or a reverberating yell; it is not primarily a religious or psychological phenomenon.

Two Dharma-heirs of Gudo, one who has never met me, one a British friend who has sat with me on numerous occasions, have recommended me in the past year or two to undergo psychological counselling. I don’t rule anything out, but I myself would never recommend others to go down that route. Both those guys seem to have taken pains not to get on the wrong side of Gudo, whom they naturally revere for bestowing the Dharma on them, but their recommendation suggests to me that neither of them -- neither the one whom I consider a friend nor the other one -- are coming from the same place as Gudo himself. They may be legitimate heirs of Gudo, legally speaking, but biologically speaking his lifeblood is not like that.

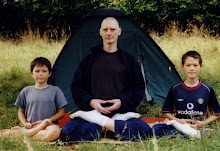

Anger is one of the three poisons, a physical thing. Being angry, I come to the forest and sit in lotus.

I never heard Gudo recommend anybody at all ever to take even one small step in the direction of psychotherapy. Generally speaking, he recommended people to practice sitting-Zen itself and to study Shobogenzo, whose root is sitting-Zen.

During solitary retreat here in France, I listen to a lot of BBC Radio 4. I like Radio 4 a lot. But everybody on it is an amateur psycho-analyst -- every news reporter or presenter of Desert Island Discs is an expert on human psychology.

Maybe it is a source of unconscious pride for we “educated” Radio 4 listeners that nowadays we have understood just about everything there is to understand in human life, on the basis of modern psychology.

Psychology is generally accepted as a bona fide science, higher up the food chain than Alexander work. In future, people may see that the teachings of both Alexander and Dogen, being concerned with acceptance and use of the whole self, are a cut above psychology.

Today I took a close-up digital photo of a robin, with which I was thrilled. Looking at the photo brought a smile spontaneously to my face. In my excitement, however, I erased the photo. I took some other photos of the robin too, but I erased the best one. It was a small loss within the greater scheme of things, but a loss all the same, and a useful reminder to me of how I am prone to react to any kind of loss -- by holding the breath.

Uptight breath holding is a strong unconscious tendency that I have observed in myself in response to many difficult stimuli along the way -- from disappointment, disorientation, and difficult choices, through to the desire to stretch out painful legs.

Isn’t the scenery of every sitter’s journey inevitably littered with these kinds of experiences -- times of loss, of missed boats; feelings of being disoriented, or seasick; frustrations, unforeseen stops at unmarked crossroads; and ultimately sheer pain, unavoidable physical discomfort?

And isn’t the tendency to restrict the breathing, when confronted with such stimuli, a universal one?

Because the tendency is unconscious, it often goes unnoticed, unless brought into awareness by an effort of attention.

According to some commentators the effort required is more than an effort of attention. There are Dharma-heirs of Gudo who have written of belly breathing -- for example, Michel Proulx and Richard Morrissey. Their advocacy of abdominal breathing shows that they have not got Gudo’s lifeblood either. Gudo only ever recommended me to attend to the matter of sitting upright, because, when we are truly upright, the breathing takes care of itself.

Of course, most of the time I am not truly upright. Alexander work made me aware of that. In general, I am more or less uptight. In that case, the traditional way is not to do something with the belly to help the breathing; it is rather to stop being uptight and get back on the vigorous road to uprightness. Then the breathing will become easier, naturally.

A few years ago during a solitary retreat here in France, I wrote the following verse:

Thirty years after school,

Here I am, still a fool.

What I feel to be true uprightness

Turns out to be just uptightness.

The two kinds of extreme response to suffering are (1) to be overwhelmed by it and collapse, as if wishing to curl up and die; and (2) to refuse to be bowed by it and stiffen up. Either response is accompanied by restriction of the respiratory mechanism; in other words, by a lack of physical ease.

Master Dogen’s rules for sitting-Zen guide us to seek that physical ease, which lies in the middle way between giving up and trying too hard. Dogen exhorts us to get the point that sitting-Zen is not meditation to learn (not “seated meditation” or “seated Zen”); it is rather a gate to effortless ease.

This search is not primarily a psychological journey. It is a search for ease in sitting -- a sitting posture that is characterized by true uprightness, which, in other words, is characterized by neither slumping nor uptightness; a sitting posture in which, after one deliberate out-breath to get the ball rolling, breathing is left to take care of itself.

Seeking ease in sitting might be like seeking a blue lotus, in which case the principle to remember might be this:

Fire does not turn into blue lotus flowers. Blue lotus flowers open in fire.

Thus, in the daily quest for true uprightness, observing Master Dogen’s rules, I attend first of all to how I actually am in my body, and where I am in spacetime/gravity. Out of this attention, eventually, on a good day, there may arise the concrete clear intention to sit truly upright, not uptight, and to sit still. Ultimately, the gap between intention and the real act of easy upright sitting in stillness, has actually to be bridged.

Is there a single criterion that covers (and not only in a linear, serial way), each of the above four bases -- emotional state, spacetime awareness, intention to sit upright, and uprightness itself?

In seeking to clarify what this criterion might be, psychology may not be the traditional place to start.

According to Gudo, the criterion is not a psychological one but a physical one: namely, balance of the autonomic nervous system.

Maybe to touch the first base is to have covered all bases already -- I don’t know. But it seems to me that to repay the old man’s benevolence requires us to clarify the criterion further, covering all bases more explicitly.

Clarifying the criterion does not mean only to write clear explanations of it; it means, as authentic successors to the Samadhi of ninety-odd ancestors (all of whom were celibate monks), to manifest the criterion in practice. To accomplish all this without falling into the trap of pride in the understanding of little me… strikes me as an extremely difficult proposition. My track record so far, clearly, has not been spotlessly free of errors.

Now I will draw to a conclusion this intended pre-amble which has turned into a lengthy ramble. My final thought is that to repay a master’s benevolence does not mean to suck up to him, out of gratitude for having received a few feet of silk certifying that Joe Bloggs is a Zen Master. Truly to repay Gudo’s benevolence is, without going against the essence of his teaching, to be clearer about the essence of his teaching than he is himself. That is the task. Regardless of our own deeply unreliable and ever-wobbling feelings as to whether or not we are up to the task, that is the task.

2 Comments:

Thank you

Jordan

Thank you, Jordan, for listening so attentively.

I had thought that my only audience might be the birds and squirrels.

Post a Comment

<< Home