(4d) Spontaneity

Everybody is familiar with the traditional Chinese image of the big-bellied happy Buddha, his vital energy sending his arms up in the air. He, to me, is a symbol of spontaneity -- Yippeee!

A thing I was taught while training in traditional karate-do is that to maintain a good strong fist you only have to be mindful of two things: the little finger and the thumb. If you pay attention to those two points, all the stuff in between takes care of itself. (But if, in the heat of the moment, you lose attention, then something is liable to get broken.)

The same may be true in the performance of a somersault by a gymnast, or in the non-performance of a non-somersault by a non-buddha -- from the raw material of delusion to Yippeee! and back again.

Master Dogen’s Rules of Sitting-Meditation for Everybody actually work in practice. If we keep coming back to them for 5, 10, 20, or 25 years, treating them with the respect they deserve, they take us reliably from here to there and back again.

There again, who am I to make such a pretentious statement, as if I were the one who knew?

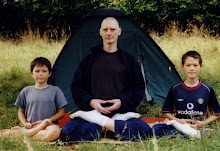

A big Zen poser, his heroic ambitions all disappointed, slinks away to the forest, to be ignored even by the birds and squirrels.

YIPPEEE!

4 Comments:

I’ll have a banana if you’ve got one going spare. Wrapped in a crepe with some crème fraiche would be nice. Wouldn’t mind a glass or three of calvados to wash it down either. Could I also have a bowl of mussels cooked in muscadet? A cup of coffee before sauntering off, swaying from side to side, for an afternoon snooze. Lovely.

Hello Pete,

I heard a Zen teacher from Liverpool called Dave Scott make an interesting contribution to Radio 4's Food Programme. He said something to the effect that the most hedonistic experience in the world was, say, during a morning of working outside in the cold on your allotment, to have a hot cup of tea.

Ah yes! That hits the spot.

As an afterthought to the post in which I invited you to join me in a banana I would like to add something. Being unable to let go of my terrible perfectionist tendency, I cannot stop myself wanting to add something. Do you see how I am? I preach letting go, but cannot resist the temptation to add something on, as follows:

To express it more simply, swaying left and right has the great virtue of reminding me that, although I can know when I am a long way off the middle way to the left or to the right, I cannot be absolutely confident of knowing exactly where the middle is.

Now, seeing that I have fallen again into the trap (into the gap, into the abyss) of writing as if I were One who Knows, a buddha who clarified everything in four phases, I direct myself back to square one.

Action is not thinking; and thinking is not thinking about, which is a kind of worrying -- which is after all another kind of feeling, centered on the vestibular system. And as a compass on the quest for enlightenment, the vestibular system, though absolutely vital, is not absolutely reliable.

Not being equipped with a reliable vestibular system, what is non-buddha to do?

An ordinary bloke is free to snooze, and free to sit. Non-buddha is free to snooze, and free to sit.

“Not being equipped with a reliable vestibular system, what is non-buddha to do?” is I suppose a rhetorical question but it has been on my mind for several days. If “the truth originally is all around…the vehicle for the fundamental exists naturally… (and) in general, we never depart from the place where we should be” why do we need a compass? I ask that sincerely, but one question leads to another. Is your quest for enlightenment a wish to attain the matter of the ineffable? Does Master Dogen mean that the practice of the ineffable is actually the attainment of the ineffable? Is the practice of the ineffable the backward step of turning light around and reflecting it? On and on the questions go! Are they what you mean by a kind of worrying?

hAt the beginning of morning sitting-meditation non-buddha finds non-buddha, again, back at square one -- unconsciously worrying, a slave to old emotional attachments and reactions.

After enduring a period like this, non-buddha feels that he has had enough of noticing "how am I?," and naturally becomes interested in "where am I?" Even though his compass may be faulty, even though it led him seriously astray in the past, still he consults it.

After consulting the faulty compass, non-buddha becomes like a punching fist, or like a monkey enjoying a banana.

But the buddha you ask about is beyond all the above, abiding spontaneously and ineffably in the ineffable. Leave him be.

To tell you the honest truth, OB, when I was in my early 20s I was so eager to grab the ineffable that I totally failed to take into account that my compass might be faulty. Hence I had abundant opportunity to investigate the truth of suffering. What was the origin of the suffering? Should I blame the faulty compass? No, I don't think so, because every human being's compass is more or less faulty. Should I blame the eagerness to grab? Yes, that was the problem, there was the gap. I was so eager to be the hero who grabbed the ineffable that I overlooked more mundane emotional matters that impinged on my happiness as a human being. I didn't spend sufficient time at square one. I didn't understand that the secret is in the preparation. My attitude was a classic example of what Alexander called "end-gaining." Whoops.

Back to square one

Back to square one

When all's said and done,

It's back to square one.

Post a Comment

<< Home